(Text by Danny Beckers)

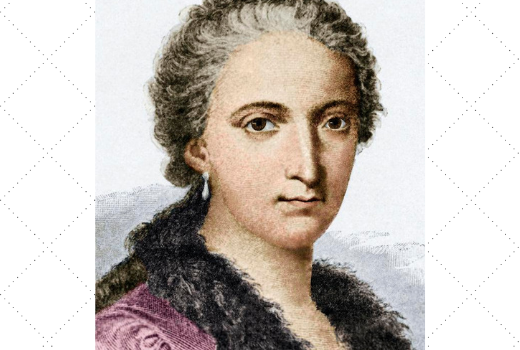

Maria Gaetana Agnesi (born in Milan, May 16, 1718 – died in Milan, January 9, 1799), famous for her textbook on calculus and her contributions to the discussions in the Milanese salon of her father. Daughter of Pietro Agnesi (1690?-1752), a very wealthy Milanese silk merchant, and his wife Anna Brivio (1699?-1732).

Maria Agnesi led her life in service of others. During the first part of her life, she spent much of her time discussing science in the salon of her father, and she was considered by many people a talented teacher and an original thinker in the mathematical sciences –in her case the present-day fields of physics and mathematics. The second part of her life, from 1752 onwards (the year of her father’s death), she turned to charitable work in the parish church and at the local city hospital. She did well in devout Catholic circles, just as she had been great in the salon of her father. In 1771, she was appointed director of the female section of the Pio Albergo Trivulzio, a new institute in Milan to house the invalids and chronically ill. It is there that she finally died of pneumonia, during the occupation of Milan by French revolutionary troops.

Agnesi may be considered a prime example of “Catholic Enlightenment”, an episode in Italian catholicism that tried to re-establish what was considered to be the “authentic church”. This involved both devotion to the one and true religion, but also included teaching of the newly discovered theories and trying to contribute to the spread of knowledge among the youths.

Agnesi’s father, however, had other objectives. He wanted to raise his family to the status of the aristocracy. Pietro Agnesi was well connected, and organising cultural soirées (evening parties) was a way of working up to his aspirations: Milanese aristocrats were among the regular visitors. It was during these soirées that Maria Agnesi stood out in discussing topics from Newtonian optics, mechanics, or mathematics. It was also there that the idea of publishing a textbook on calculus for the Italian youth was born. Several manuscript versions of chapters from the book were discussed among the aristocratic friends of the Agnesi family, before it was finally published in 1748.

Later in her life, Maria Agnesi reflects on this episode, and feels she was living up to the expectations of her father. Her new life (which she took up shortly after he died in 1752) offered her more joy. Whether this was hindsight speaking – she vigorously defended the right for women to make their own choice in education and occupation during her father’s soirees, so she could speak her mind publicly – or whether she was really living her father’s idea of life is hard to tell. Either way, her father’s soirees were fruitful: Agnesi was allowed to attribute her calculus textbook to the empress Maria Theresa of Austria. Maria Agnesi used a clearly feminine rhetoric in her attribution:

“Among the various arguments I revolved in my mind, inducing me to hope, that Your Sacred Majesty, according to your great condescension, would vouchsafe to receive favorably this work of mine, which is proud to shelter itself under your August name, and humbly to crave your gracious patronage and protection; among all these arguments, I say, none has encouraged me so much as the consideration of your sex, to which Your Majesty is so great an ornament, and which, by good fortune, happens to be mine also.”

Although she was offered a professorship at the university of Bologna in 1750 (via the pontiff himself), she declined. It is hard to tell whether that was a first attempt to leave behind the life her father had chosen for her or whether the position was simply considered below her standing.

Nevertheless, Agnesi is (or deserves to be) well remembered, next to several contributions to the scientific culture of her times, for publishing a great calculus textbook. Her book was translated in French (1775) and English (1801), and thereby spread over Europe. It was by far the most widely used calculus textbook until in the nineteenth century when it was pushed from the market by more modern books. In Italy, it was even so well-known that her book appeared in a popular theater play!

Archives:

The archives of Maria Agnesi are to be found in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana Milano, the Archivio di Stato, Milano and the Archivio della Parrocchia di San Nazaro Maggiore.

Works:

Propositiones Philosophicae, Milan (1738)

Instituzioni analitiche ad uso della gioventù italiana, Milan (1748) [in four books]

Literature:

Paula Findlen, Calculations of faith: mathematics, philosophy and sanctity in 18th-Century Italy, in: Historia Mathematica 38 (2011), 248-291 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0315086010000315)

Massimo Mazzotti, Mathematics and the making of the Catholic Enlightenment, in: Isis 92 (2001), 657-683 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/3080337)

Massimo Mazzotti, Maria Gaetana Agnesi: Science and Mysticism, in: U. Lehner and J. Burson (eds.), Enlightenment and Catholicism in Europe: a transnational history, Notre Dame University Press (2014), 289-306 (https://www.academia.edu/8290504)

Rebecca Messbarger and Paula Findlen (eds.), The contest for knowledge: debates over women’s learning in Eighteenth-Century Italy, Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2005). DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226010564.001.0001

Clara Silvio Roero, M.G. Agnesi, R. Rampinelli and the Riccati family: a cultural fellowship formed for an important scientific purpose, the Instituzioni analitiche, in: Historia Mathematica 42 (2015), 296-314 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3080337.pdf)